In 1937, occupied with “proof-reading, folding printed sheets, hounding delinquent clients, [and] writing letters and even introductions to books” in her husband and brother-in-law’s Grabhorn Press, Jane Bissell Grabhorn “suddenly revolted and decided to do some printing of her own and by herself” (Grabhorn “Mea Culpa”). The act of revolt on Grabhorn’s part would become just one instance of many in which she would defy expectations through her printing enterprise, the Jumbo Press, which she operated single-handedly from 1937 until her death in 1973. Employing typography and print to express feminist thought processes in her hand-press productions of satire, wit, and ephemera, Grabhorn exclusively utilized letterpress printing as a place of rebellion. As Grabhorn notes in her 1937 A Typografic Discourse, a piece originally published as part of the volume, Bookmaking on the Distaff Side, her press realizes the ways in which women’s work might reimagine the male-dominated sphere of printing and its influences: “Jumbo stripped the mask from typography’s Medicine-Men and their disciples have seen them as they are: —pompous, tottering pretenders, mouthing conceits and sweating decadence” (8). Grabhorn’s perspectives on the art of printing itself would prove to continually subvert expectations of women’s roles—and more importantly, the increasing relevance of the female printer’s place in printing history.

Through an analysis of Jane Grabhorn’s writings in Lois Rather’s Women as Printers, as well as an examination of Grabhorn’s The Compleat Jane Grabhorn, I argue that Grabhorn’s contributions to printing serve as a feminist activity to metamorphoses the press as a tool for promoting social change. By utilizing print to materialize her findings of the social and cultural environment, Grabhorn and her contributions provide a new way in which to examine the role of print and the printer entirely through the lens of female work. In identifying the types of feminist activity Grabhorn participates within, I believe it is important to first establish the so-called boundaries of what feminism might be for this topic, though it is my no means exhaustive. Contrary to Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, the book which inspired many of the explorations of how women might find a destiny greater than that of “their own femininity,” Grabhorn’s feminist project predates—and in many ways, becomes more subversive—than that of her second-wave successors. Grabhorn casts off the imagined place where male roles must be the dominant presence in printing practice: early in her tenets for the Jumbo Press, Grabhorn encourages women according to principles that purposefully subvert the “rules” known of printing. She notes, “Don’t be tied down like dunces and fools / To quads ems picas and man-made rules. / In this kind of trif-eling, let the male wallow, / For women the freedom of wind and of swallow” (10). Like modern feminists, including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose work has grappled with the importance of reclaiming the language of feminism to evoke equity and progress, Grabhorn envisions her feminism through letterpress printing as a form of reclamation of words and the ways that they are used in the production of language.

Despite Grabhorn’s vision of printing, the image of the male printer standing beside his press with a pipe in his mouth often remains the prominent representation of the individual involved in early-twentieth century press work—indeed, the Kelsey Company’s Printer’s Guide depicts just this. Yet Grabhorn’s earliest work, A Typografic Discourse, republished by the printer in her 1968 The Compleat Jane Grabhorn, subverts this image by prompting her reader’s view of an alternative option for whom the title “printer” might encompass. When encountering the type case, this printer “roots around until she finds something she wants,” undisturbed by the rules enacted to provide order (10). She might toss aside hyphenation simply because of the “beautiful logic of such procedure” and the ways in which avoiding the mandatory grammatical rule emphasizes “qualities so peculiar to the female—courage, imaginativeness, adaptability, & the will to experiment” (9). Most importantly, she recognizes that it is a “folly to waste much time” on the names of all of the typefaces, the theory of type sizes, and what traditionally goes well together visually no matter the satisfaction it might bring to graphic design. Instead, the capabilities of this alternative printer—the female printer—must move away from the limits imposed on printing and introduce creative license. This is what makes Grabhorn’s printer wholly independent from her male counterparts. Although in constant collaboration with the primary male figures around her in her life of printing, Grabhorn’s envisioned place—and subsequent reality—of her role as printer allows the equity paramount to feminist ideals.

While studies in the histories of printing and the book have recently come to acknowledge women’s contributions, comprehensive examinations of their work first occurred only during the period of second-wave feminism in the United States. Fine-press works, including Lois Rather’s 1970 Women as Printers, examines the place of women across print history, yet many figures who directly influenced the use of printing for feminist purposes remain unrecognized for their contributions in Rather’s examination. Beyond her brief remarks from correspondence with Rather, Jane Grabhorn’s role in the feminist action of printing remains undisclosed in this volume. Yet her comments about her role as a printer in Women as Printers make the clearest point of Grabhorn’s distinctive approach to her role. She accentuates her affection for the dirty hands and labor required for printing, and most importantly, her admiration for the physicality of the object created by the labor itself. She describes that she has “always been a little contemptuous of people who call themselves ‘designers,’ who seem to think this is more artistic and do not want to be thought to be lowly laborers” (Rather 69). Rather than being defined by the supposed ineptitudes of female printers, highly recognized in nineteenth- and early-twentieth century commentaries about the prospect of women in the print shop, Grabhorn makes a point to note the relevance of her own labor in press production. The act of producing “the book” becomes the act of beautiful fabrication possible in women’s hands. As Grabhorn explains, “When I am putting [the book] together I am creating it. It is shaping up before my eyes and in my own loving hands” (70). No longer the object of masculine creation, the future of the book and print is resoundingly possible in terms of femininity as well.

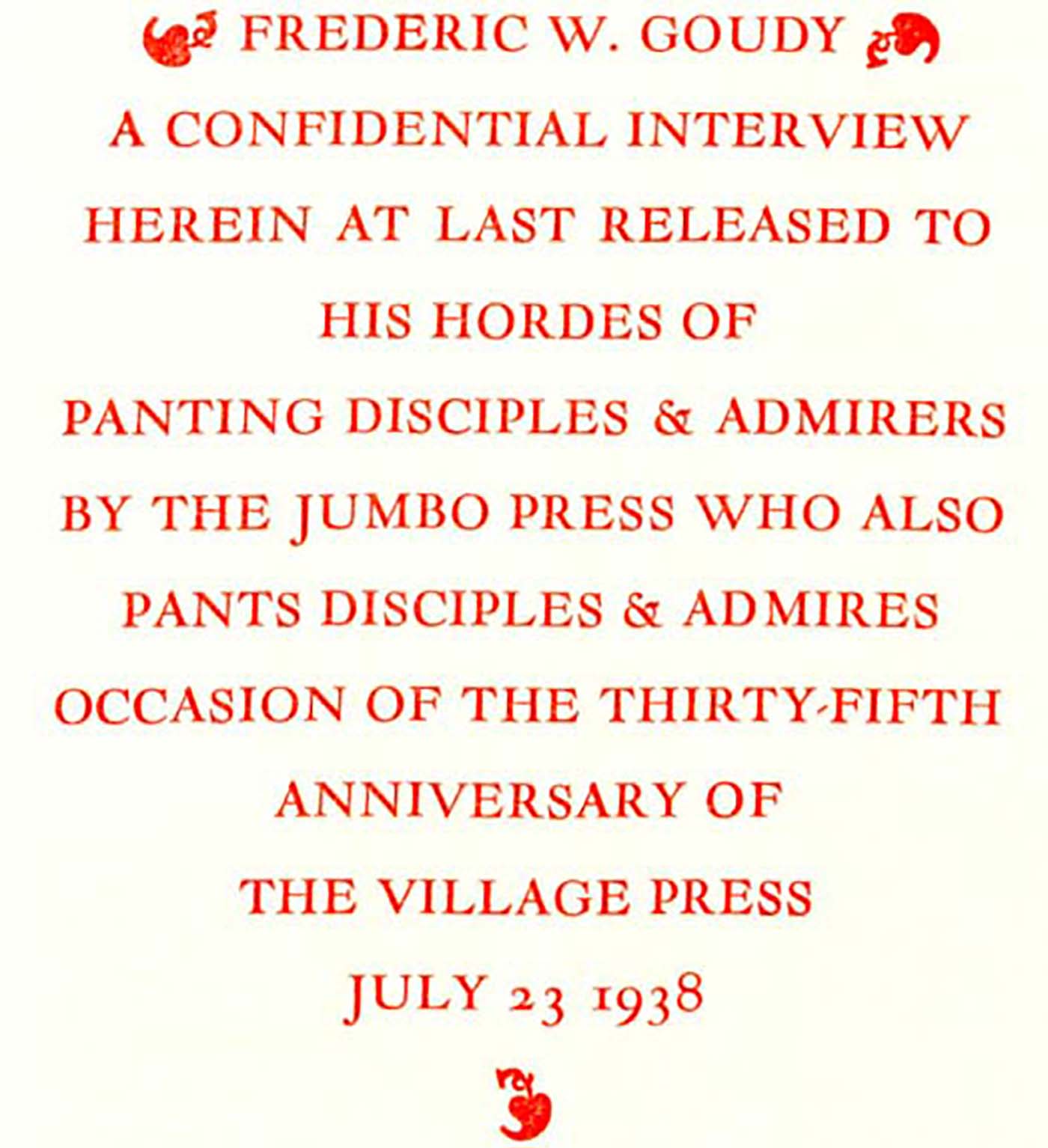

In Grabhorn’s “loving hands,” the Jumbo Press provided an opportunity to speak to the issues that might plague female printers of the twentieth-century. Beyond arguing against “typography’s Medicine-Men and their disciples,” Grabhorn similarly described her own role as a printer of her Jumbo Press production. She did not print “in the spirit of humility,” but rather in the “spirit of defiance and self-defense” (Grabhorn 48). Unlike the larger imprint of the Grabhorn Press, Grabhorn’s personal printing work through the Jumbo Press did not garner high prices at the time of their production. The Jumbo Press’ successes, however, might instead be measured by their subversive qualities against the traditions of printing history. Grabhorn’s printed works deal with a variety of topics, including her own “confidential interview” with Frederic W. Goudy— “at last released to his hordes of panting disciples & admirers by the Jumbo Press who also pants disciples” (31). The seriousness provided to Goudy by type and print historians is easily satirized by Grabhorn, who describes the imagined encounter of a luncheon with Goudy. Grabhorn, fashioned as Jumbo, poses a number of questions about the “correct” process of printing to Goudy, asking him about type, fonts, and paper, only to be answered with commentary not at all related to print itself. In place of providing Goudy importance and omniscience within letterpress history, Grabhorn suggests that the type of worship applied to figures of his caliber be taken less seriously, and to instead prioritize the power of the individual printer by their own terms.

The ability to subvert the expectations of discipleship through the medium of print is what often sets Grabhorn apart from her contemporaries: she has few qualms about poking fun at revered fine-press printers, and successfully draws attention to the unequal measures for which printing success is understood. In providing both the measures for female printers to destabilize the traditions of fine-press printing, as well as to undermine the serious devotions to prominent printing figures, Jane Grabhorn encourages an understated form of social change focused on—yet not limited to—printers of the twentieth century. In her earliest printed work of A Typografic Discourse, Grabhorn describes the printing as coming forth from her “typographic laboratory” rather than describing it in terms of its actuality as a press. The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “laboratory” in this instance is particularly useful for understanding the types of social and behavioral changes Grabhorn inevitably advocates for in her printed work. The general term of “laboratory” is “likened to a scientific laboratory, [especially] in being a site or centre of development, production, or experimentation” (“laboratory, n.”). Grabhorn’s site of “development [and] experimentation” is paramount to the alterations in social views towards women as printers which Grabhorn counters in her printing “laboratory.” The “qualities so peculiar to the female” are those which similarly allow changing perspectives about female printers themselves (Grabhorn 9). The “will to experiment” in the “laboratory” print shop provides an opening into the previously male domains of production, encouraging alternative expectations for what and whose experimentation is acceptable.

Grabhorn’s broader influences in social change through altering conceptions of what a successful printer is can be most successfully realized in an early form of second-wave feminism—one which realizes reclamation prior to the feminist movement of the midcentury. Compared to the first-wave feminists, including Mary Wollstonecraft or Charlotte Perkins Gilman who encouraged equality in women’s education and improvement, Grabhorn’s version of feminism expands the early twentieth-century ideal of the “social awakening of the women of all the world” (“As Mrs. Gilman Sees Feminism”). Grabhorn’s feminist efforts expressed in her collected The Compleat Jane Grabhorn are those which inspire the types of social change which would be indicative of the second-wave feminist movement nearly twenty years after Grabhorn’s A Typografic Discourse. Her evocation as a feminist might be imagined by her discordance with the domestic lifestyle required for twentieth-century women. Grabhorn herself noted her own questions as to “whether [she was not] missing something” in pursuing the life of a printer, publisher, and bookseller (Grabhorn 42). But, as she notes, “I am so used to seeing my hands look like hell, to having a smudged face, and no time to get my hair fixed, to wearing dirty, frayed smocks” (42). Gone is the requirement of adherence to a life of domesticity, and instead, Grabhorn invokes an interest to “revert to type” in a life where evocative and subversive progress is acknowledged. Grabhorn created the space to subvert the expectations of her femininity in the twentieth-century imagination: in the end, being a “printer-publisher [was] really [her] conception of the ideal existence” and provided an imaginative space for other women to create their ideal existences as well (42).I’ve attempted, in my exploration of The Compleat Jane Grabhorn, to provide an overview of the type of generative labor that Jane Bissell Grabhorn undertook in her life’s work as a printer and publisher. Between her jobs as writer and copyeditor, typographer, compositor, and even binder for her husband’s press as well as her own, Grabhorn crafted a place in print history which emphasizes the inquisitiveness necessary for the future of knowledge production. As Grabhorn’s printed works from The Compleat Jane Grabhorn reiterate the importance of freeing language and print from society’s confines, the re-envisioned image of the printer, and engagement with ideals which would remain paramount to the feminist movement far beyond her historical moment. The printed works discussed provide a form of exploration counter to what we might traditionally understand as “printing history”—but I believe this in itself is central to Grabhorn’s efforts in reclaiming, with “loving hands,” the opportunities that could be figured for realizing women’s place in the print shop. Not confined by hyphenation, technique and its pitfalls, or correction to ensure her own creative capabilities, Grabhorn creates the new figure of what the printer has the potential to be: broadly speaking, women “well-suited to being printers” (40).

I would like to conclude with what I find the most meaningful of Grabhorn’s descriptions of female printers. In an area of work where men’s labor and ingenuity was prioritized by individuals of the past, Grabhorn’s view of the female printer is a valuable example of how we might instead think of women in print history today: as the forward thinking, valuable figures that they so-often were, are, and continue to be. The female printer is “strong and unself-conscious, a quite natural creature who never minds being dirty, and usually is. Her hands are capable and sturdy, and her mind direct and uncluttered by the longings which best most females; consequently she is able to bring to her work the patience and concentration which such work demands” (41). Through type, press, and language itself, the female printer speaks—even when her voice has the potential to be silenced.

Works Cited

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “What is ‘Feminism’?: As Mrs. Gilman Sees Feminism.” Atlanta Constitution, 10 December 1916.

Grabhorn, Jane. The Compleat Jane Grabhorn. The Jumbo Press, 1968. Located in Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

“Laboratory, n.” Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press, September 2019. Web. 25 October 2019.

Rather, Lois. Women as Printers. The Rather Press, 1970. Located in BookLab, Department of English, University of Maryland.

![Jane and Robert Grabhorn [n.d.] (Book Arts & Special Collections, San Francisco Public Library)](http://www.alphabettes.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Grabhorn3-1.jpg)