This is a transnational call for solidarity with the Palestinian people and a call for an immediate and permanent ceasefire in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. A ceasefire – not a pause, nor a truce – is not the only demand, but is the first demand. Starting (and expanding) from the 153 countries that have signed the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide; we say Ceasefire Now! If you wish to contribute from a place/in a language that is not yet covered, with your typeface, lettering or calligraphy, head here. To print and post/make placards with the poster head here. This post is updated every other week.

Continue readingCategory → Commentary

Who is an industry leader?

Who is an industry leader?

What makes one qualified to use this title? Is there a certain amount of time someone needs to be professionally active in a field to call themselves one? Is it others’ perception that matters? How are these concepts tied to gender, class, race, geography? Why do structures exist to perpetuate the use of the term and why do we think this is acceptable?

I’ll be sitting here thinking about these questions while sipping my tea.

Font licensing, webfonts and fair trade

A few weeks ago, I had to advise a design studio on licensing fonts. It is a common practice since different foundries and distributors handle licenses in many alternative ways. What may be complex for us, who work in the type industry, can become a nightmare for font users and design studios that acquire licenses for their clients. Some have made an effort in simplifying font licenses but webfonts is still a case worth discussing.

From all the types of use you can make of fonts, the web is probably the format where we find more differences, both in the licensing model and the pricing. Some articles offer information on the topic and compare the different licenses available. I was surprised to note there is little debate or discussion on this.

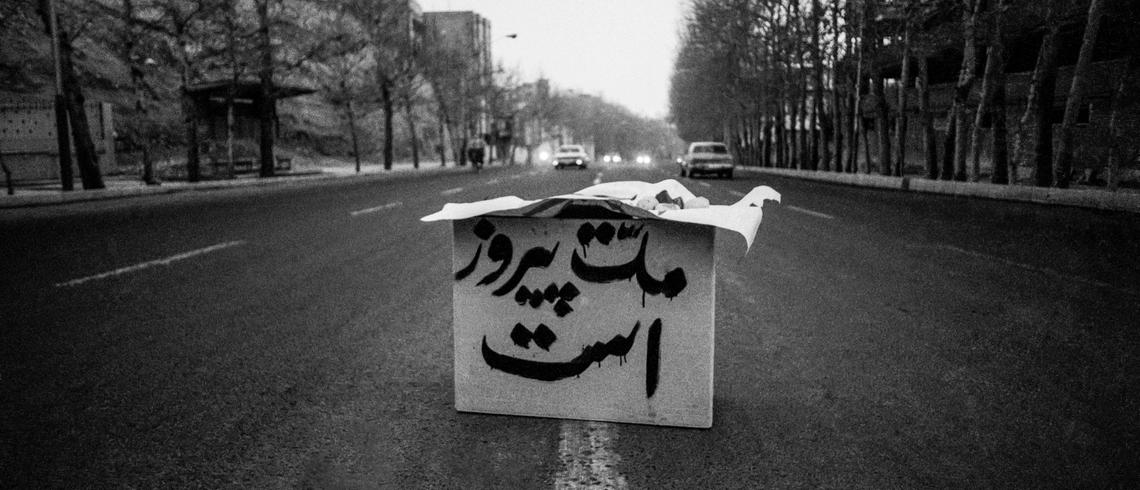

Continue readingProtest Scribes

Protest art refers to the artistic works created by activists and social movements. It is a traditional means of communication used by a cross-section of collectives and the state to inform and persuade citizens. The slogans of the revolution, movement, or demonstration are written on walls and buildings while the writer is in distress. This usually occurs at night in the cover of darkness. The scribe is not worried about letterform correction or aesthetics, they aim only to express themselves by writing their thoughts on the surface and informing the public. But their action surpasses this; they are creating art. They represent a specific cause or message from furious people that need to be heard. Protest art is an essential technique for increasing social awareness and developing networks. It has long been a powerful platform for conveying ideas to the masses, as it can promote conversation and highlight social, political, and environmental issues.

Thai Type Tourist

The population of Thailand is around 70 million people, 11 of them living in Bangkok alone.

Thailand is home to 71 living languages. The 2014 Ethnologue country report lists one national language (Thai), one educational language (Isan), 27 developing languages, 18 vigorous languages, 17 threatened languages, and 7 dying languages.

“Thailand has experienced the gravitational pull of Europe over the agitations to do with becoming ‘modern’. Yet, it has never been formally colonised” by Rachel V. Harrison and Peter A. Jackson.

On July 19th, my partner and I moved to Thailand for one month while working remotely.

Continue reading

New borders: the working life of Elizabeth Friedlander

I first heard of Elizabeth Friedländer in an article about early female typeface designers. Using some of the typefaces mentioned in the text I decided to prepare a few images for our Instagram account. That personal exercise opened the door to extra information about the names included in the article. There was an exhibition on Elizabeth’s work at the Ditchling Museum (England), and Katharine Meynell had released the film Elizabeth in 2016. While looking for more information about her I also found the book I am writing about today. This book, letterpress printed and bound by hand, was published as a limited edition of 325 copies. A couple of months ago—coinciding with the launch of Women in type—I finally found it online and was able to read it. The University of Victoria Library scanned the pages and made the book available for all.

The book is full of reproductions of her work, not only finished and published projects but also drawings and documentation of her design process. The author tells us about her life’s path, moving from one country to another, and finding ways to nurture her career as a designer. The text includes insightful quotes from personal documents and imagery from the material she carefully preserved, allowing us to know about her work and career through primary sources.

Rough work in Indian ink for different projects

How to find your inner compass as a lettering artist

Recently, Dominique Falla asked me to be part of Typism’s new podcast series, and talk about the concept of inner compass. After the recording was done, I realised that the notes I prepared for our interview could be valuable for many designers in the visual communication field, and not only for the ones interested in lettering. Below are my notes for anyone who’d find that useful.

What exactly is an inner compass?

For me, an inner compass is a set of principles to guide you through life and work, and to help you understand what things work and what things don’t work for you.

Reflections on THAT article

One of the things I have thought about since that article came out is why I read that article the way I do, and why others did so differently. I am someone who would both benefit and is restricted by what this article puts forward as an action in point #4. How do I deal with this contradiction? India is home to a lot of scripts and languages. I have lived in various parts of the country and in doing so have had to learn a few of the languages spoken in those parts. My fluency in those languages today is at varying levels. How do I engage with the many scripts that I am familiar with? Can I design for one of the native scripts that I grew up with, which is different from the one I am most comfortable with? Everyone’s worldview affects the way they understand things and I realise how mine has affected my own understanding. This point makes me uncomfortable too. So I push myself to sit with this discomfort. Which is what has brought me to try and view this contested point #4 in non-binary terms. When people are expressing themselves in unfamiliar ways, I assume that my work is to understand their point and that healthy boundaries are essential for everyone to flourish. Allow me to explain this further.

Continue readingReflections on “It’s Time to Act”

Alphabettes is a diverse group of women from across the globe with a variety of backgrounds, views, and life stories. The article “It’s Time to Act” is an example of a collaborative effort aiming to respond to recent events and to raise difficult questions that our industry needs to engage with. Difficult questions are by nature controversial and are often highly emotive. One such question is the one raised in point 4 which calls for designers to stop taking design commissions for scripts they did not grow up with. This article will examine this issue and focus on 3 key questions: Is a designer able to design for a script they cannot read? If yes, should they? And finally, how can we as an industry support designers who come from disadvantaged backgrounds?

Continue readingIt’s time to act

The Alphabettes community is, at its heart, political. We are a global network of women, connected together by our love of letters, type, and typography. Our objective is to champion anyone who identifies as a woman in type, provide a platform for them to show and share their work, and welcome them to a community that will not ignore their voice, but amplify it. Alphabettes started through the joint effort of Indra Kupferschmid and Amy Papaelias in 2015, and since then the network has grown to include over 245 members worldwide. As a community, we aim to respect and reflect on the opinions of all of our members, and we continue to learn and grow together.

During the last two weeks and following the tragic murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis policemen, the United States of America saw a powerful uprising opposing discrimination, violence, injustice, and systemic racism against Black people, the impact of which quickly rippled through the rest of the world. In a time when much of the world has retreated into their homes and maintaining social distancing has become a necessity for health, the urgency of protesting racism and discrimination and demanding justice has eclipsed a quiet survival. Since then, crowds of protestors have taken to the streets, statues glorifying racial bigots have been pulled down, and social media platforms have seen an overwhelming sharing of educational, supportive, and encouraging discourse regarding this call of eradicating racism. Donations have been made to individuals and organisations supporting this movement. No action is too small.

Continue reading