A detail from the Graphic Means official poster.

If you were a part of this era, but especially if you weren’t, you must see Graphic Means.

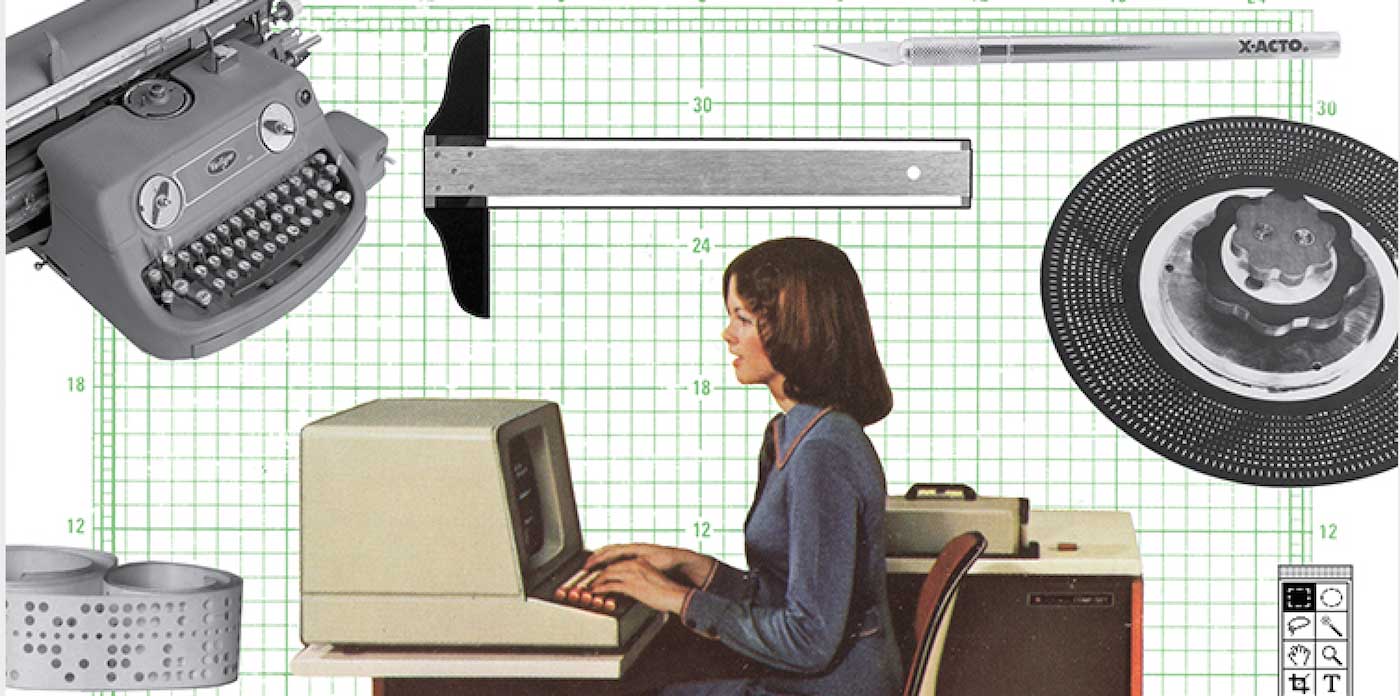

These days, it is easier to find information regarding printing in 15th century Europe than graphic design processes in the United States during the 1970s and ’80s. The latter, the focus of Graphic Means, was a major transition for the design and printing industry as centuries old procedures and machinery made way for photographic processes and eventually digital technology. This dramatic shift has not been well-documented, perhaps due to the quick speed of the conversion or that it is still in recent memory.

Graphic Means is long overdue, both as a historical document and a design reference. The production standard was visibly high and the stills, vintage education reels, and interviews harmoniously interwoven. The film was informative and even riveting, and I say this with having known the story, and the ending, first-hand. The only questionable aspect of the documentary – and this is so minor that it’s negligible – was that at times the music felt discordant to the scene rather than contributing to it.

There aren’t many contemporaries for Graphic Means other than the flawed decade-old Helvetica and the equally flawed but more recent Sign Painters. Both were brave attempts at communicating hidden industries, both had moments of excellence amidst misleading segments, but both left me feeling that they were unfinished. Fortunately, Graphic Means doesn’t fall into this category as it came across as exceedingly thorough and properly balanced.

A notable aspect of this documentary was the gender-balance in both the interviews and the historical promotional materials. (One hopes that more will follow this lead.) Women were more than a solitary token, they were a substantial proportion, possibly half of the resources. Graphic Means also covered the cultural context of the technological and production changes, which, though essential for understanding, is often omitted from historical descriptions.

Designer, educator and 2013 AIGA Medalist Lucille Tenazas interviewed in Graphic Means.

As a person who learned the ropes ‘the old way’ during the 1980s, even I was amazed at the complexity of the procedures. I had forgotten about the back and forth between vendors and the mountains of supplies and the incessant phone calls and revisions. I was reminded how terrible I was with some of the manual skills, of my many scars from errant x-acto blades, and the frustration of aiming for pre-press perfection. However, along with all the horrors, I was also reminded of how much I enjoyed the creation of an actual object, of tactility.

During the past 30 years, I’ve experienced the dramatic changes of my profession and I remain eager for what is yet to come. My hope is that the next professional revolution will be documented at the same exceptional level of Graphic Means.

Graphic Means is directed and produced by Briar Levit. For more information or to see the film, check out the screening schedule with dates and venues around the world.