In Hong Kong, I have seen several small stores selling colourful replica of contemporary luxury made by paper, spread all over the mega city. Mimicked handbags of must-have brands, smartphones and even favourite dishes of Hong Kong dining are artfully recreated, and sold to be offered to ancestors by burning the paper artefacts. From time to time, I observed people burning the offerings in metal barrels at the backstreets.

The tradition of paper offering is an inherent part of the Chinese culture, in which the afterlife is expected to be a mirrored version of this mortal world – with the consequence that decedents are longing for material goods as we do, and they need money to trade. To worship ancestors and deities does not only lead to the enhancement of one’s karma, but allows one to ask for favours, support or advices. The act for transaction between this world and the afterworld is done by fire – as there are “no pockets in a shroud”.

While all the fancy goods, following global, seasonal and technical trends, are omnipresent in the specialised shops, the dollar notes (the paper money) are rather inconspicuous. They do not follow trends or keep a consistent design.

Different designs of paper money at the small Sheung Wan store. Below the banknotes are bundles of blank paper money.

The paper money seems to have a specific role among the big range of paper offerings. From early on, even before the invention of paper money for this mortal world, paper was used to represent money in the offerings. During the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 25 AD), paper was invented in China and became widely used by the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD). As burned paper is almost impossible to be verified by archeological means, the exact date when paper was introduced to represent money for offering is hard to say. Excavations have brought up clay substitutes of shells, gold and coins used for offerings from the first century onwards. By the seventh century, the ritual of paper offering was mentioned in literature. Multiple coins were printed on paper to indicate the value. While in China, paper money as a currency for this world was introduced in the 9th to 10th century, it was only by the 17th century that countries in Europe introduced paper as a payment media. This means, paper money used for worshipping was probably the forerunner of banknotes.

One afternoon, I bought eleven different designs of notes that I found in specialised shops in Hong Kong. Each design comes in a bundle of notes. Eight of them were sold as a set and share the same size of 155 x 73 mm. The other three vary slightly in sizes. The banknotes represent a wide range of value: 50, 100, 500, 10.000, 100.000, 1 Mio and 50 Mio. All notes share one thing in common, the portrait of the mystic Jade emperor (玉皇大帝). The paper is rough, cheap and those from the set have an open texture at the back, reminding me of recycling toilet paper. Most of the front-side layouts are printed with four colours, while the back side is in one colour and in low contrast. The print is not positioned precisely, so the cropping varies. Some of the notes are extremely colourful, carrying images of Disney style villas. The currency varies from American, Australian, British to European Euro. Some notes carry bilingual information, while others are only in Chinese. The money for the afterlife or the “ghost money” is not only borrowing the values of foreign currencies, but also the design of the international banknotes. Among the eleven notes, one stands out for its simple design. Regarding the choice of colours as well as the layout, it is obviously inspired by the old American 100 Dollar Bill.

Most information on this bill are set in Latin letters. Chinese characters seem to have a rather decorative role in this layout. A bold 萬 in a heiti (Chinese sans serif) is added one time in an extended and four times in a condensed weight behind the numeral 100 in a serif face. 美元 in a geometric sans serif style is set vertically and means American Dollar. Next to the two signatures (in two different script typefaces) on both sides at the bottom are Chinese chops by the director (left) and the associate director.

While the front side shows the effort of a designer to come up with a layout for a note of the Hell Bank strongly inspired by the US dollar, the backside can be seen as a simple copy of the text and the image (Independence Hall). Only the design of the frame and the value is redesigned.

Two terms appear regularly on the banknotes; the Chinese term 天地銀行 for “bank of heaven and earth” (or 天地金庫 meaning “treasury of heaven and earth”) and the English terms “Hell Bank” or “Bank of Hell” (冥國銀行). The usage of the term “hell” is said to be based on a misunderstanding, as Christian missionaries claimed that non-Christian will be send to hell after life. “Hell” was therefore interpreted as the general name of the afterlife-location.

The attempt to scan the Chinese paper money for offering has shown another interesting aspect. Some of the notes were obviously regarded as real money by the scanner and the scan was interrupted by white stripes. In fact this design has a great similarity with the Japanese 10.000 Yen.

Writing all this, I see different doors opening up for further research topics, as this is just a start and personal introduction to the topic. But one thing is for sure, the market for the dead is a financially powerful field, that is concurred by the capitalism and owned by the Bank of Hell.

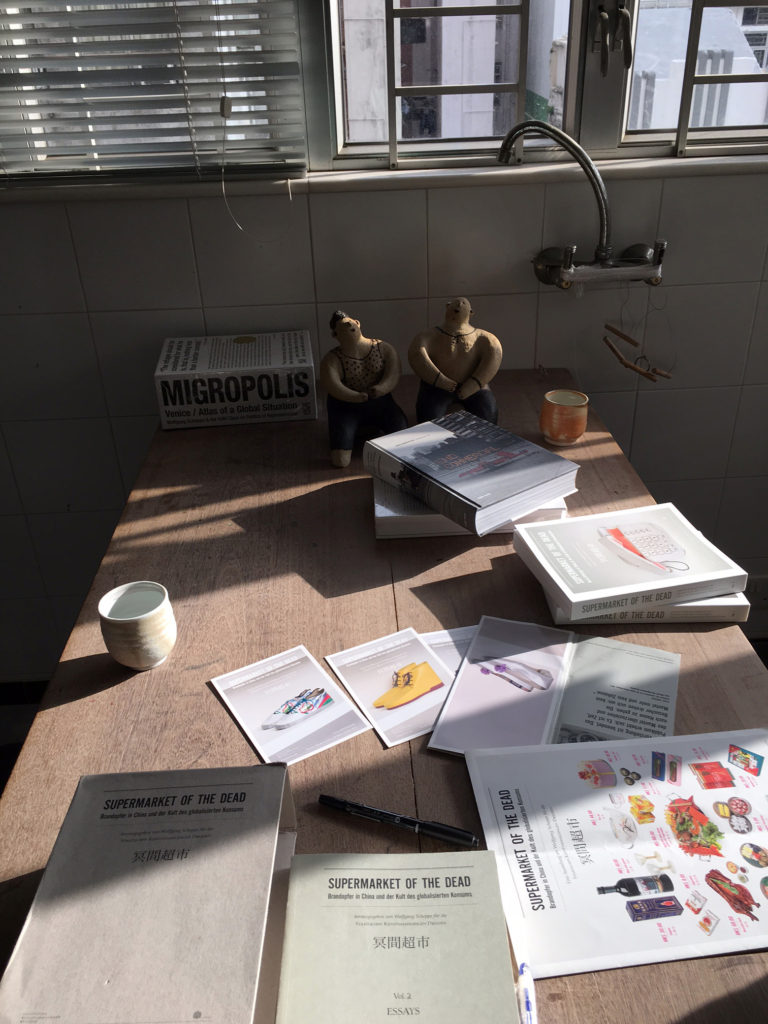

Side note: As a preparation for this article, I visited, together with the Hong Kong ceramic artist Rosan Li, some narrow streets in Hung Hom, the neighbourhood of her studio. In this area, death is the main matter of business. One shop after another sells Paper Offerings. Rosan is a collector of paper shoes and participated with her collection in a grand exhibition called “supermarket of the dead” at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden from March to May 2015 in Germany. In 2000, Rosan started her collection of paper shoes as a counteraction to the mass consumption. There is a vibrant fashion industry for the dead, and although it is less than for the alive, the industry comes up with new collections twice a year. Being a responsible collector, Rosan’s counts 600 pairs of her own by now.

References:

www.nbbmuseum.be/en/2007/09/chinese-invention.htm

Shape, Wolfgang (ed.) Supermarket of the Dead. Walther Koenig, Cologne, 2015.

This post is part of My 2¢, a short series on money-related type and lettering examples, stories and thoughts. You can read the rest of the series here.