Perhaps it is because we live in an age where styling and self-promotion shape how and whether we revere design, that the austerity of this book, and indeed, Carol Twombly’s life and career, feel so other-worldly. Which is not to say that Twombly is somehow weird or that this book about her life and work is lacking. In fact, the book is very well-written and — dare I say it, (this is a type nerd book after all) — quite an engaging read.

Here is a quick checklist of things this book offers in abundance:

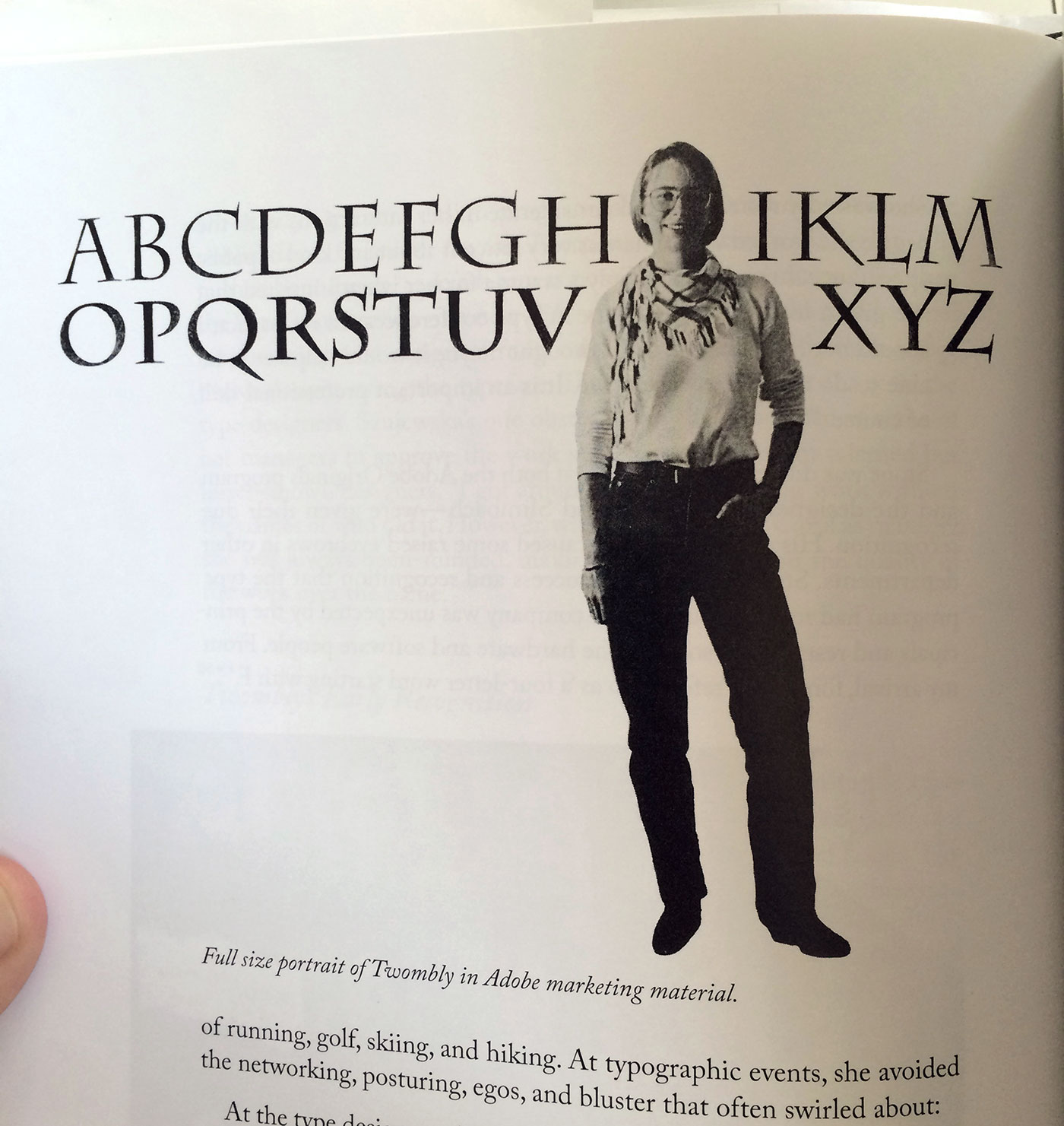

• Amazing black and white photos of nerds in the ’80s

• Descriptions of Twombly’s painstakingly precise approach and design process

• Photos of work-in-progress notes jotted in really beautiful handwriting

• Reverence from her peers testifying to her talent that is borderline protective

• Juicy tidbits that tastefully stop short of gossip about the first ten years of Adobe’s type design department

• Kudos to luminaries like Gudrun von Hesse and Fiona Ross

• The sense that Twombly is a delicate, quiet, shy rarity.

It is this last point that I will not dwell on, but that pervades the entire book … more on that in a minute.

The foreword is titled “Women in Twentieth-Century Type Design”, and it’s an excellent way to start the book, chronicling details of early type production processes we don’t hear much about, but that were chockfull of female workers. It describes the chores of making type in metal and photo — we haven’t lost an iota of number of chores, evidently — that never gets boring because it is tied to the women, companies and foundries for which these tasks were crucial. It’s a shout-out to the women who’ve tended not to get much recognition, as well as a necessary nod to Fiona Ross’s all-lady multi-script type team at Linotype in the early ’80s.

Left to right: Georgina Surman, Lesley Sewell, Sarah Morley, Gillian Robertson, Ros Coates, Fiona Ross, and Donna Yandle

The last sentence of this section feels incongruous, however: “Twombly is wary of her story arousing any renewed notoriety or unwanted personal attention. She fiercely values her privacy and for that reason she asks those interested to please accept that all she wishes to say about her career is in these pages.”

My reaction was, “whoa! This sounds like trauma! Here we were, jauntily breezing through type history’s ladies in this really positive way and now we have this seemingly disconnected statement. Okay. Welp! Let’s respect that! I hope the book explains why!”

It doesn’t. And that’s not a criticism of the book; the prose barely even hints at the impropriety such a statement suggests. So we are back to the last point on the checklist, that Twombly managed to build a formidable career despite what I imagine to be a flinching, birdlike fragility that many good people protected in order for her to be able to work.

The book features extensive quotes from Twombly, which is satisfying given her wishes to stay out of conversations about herself. In them she is always careful to note those good people who fostered her education and development in type design. In one section about the recognitions she’s received, she takes the opportunity to highlight the many women whose work inspired her and those who taught her the technical aspects she needed to learn. It is notable that she used this space to give them that recognition.

Twombly also has warm words to say about the co-founders of Adobe, where she worked for a decade in the type design department. Here was where her most notable typefaces were drawn, produced and sold, evidently earning her enough money (she invested her royalties well) to leave her career most of us would consider prematurely.

The book was designed by its author, and I was disappointed at first by what I see as a missed opportunity to put Twombly’s classic faces to more interesting effect. But after I finished I decided it’s an apt visualization of the enigmatic austerity of the book’s subject.

Overall one gets the sense that the success of Twombly’s career has as much to do with her talent as it does with the special circumstances that fostered her growth: supportive teachers in college, supportive mentors who gave her her first job, and supportive administrators, who shielded someone whose personality may not have withstood such an industry otherwise.