More than 25 years ago, while traveling in Scotland, I watched an elderly gentleman chisel a name into a black granite gravestone. He sat on a stack of upholstered stools; he held a chisel in his left hand, a mallet in his right. The craft and care he took with each and every letter seemed reverent. Each cut of the stone seemed important. Holy, almost.

Last year, the mental image of that white-haired man came back to me. Perhaps I thought of him because I had seen beautiful images of carved stone on Instagram (…I’m talkin’ about you, Nick Benson). Perhaps my subconscious craved a project that required craft and care and reverence. Perhaps I yearned for something slow and tactile as an anecdote to crass shouting, hyper-speed social media, and the mercurial leadership that permeates life right now.

Late one night I searched for a stone carving class. Options in the United States were limited; options in England were not. A business called Ministry of Stone in Lincoln offered exactly what I hoped to find: a class on carving letters for absolute beginners. At the time my calendar was filled with book promotion obligations, but I blocked time off in May and claimed a place in one of the three-day letter cutting courses.

Ministry of Stone is run by Eilidh Fridlington. Eilidh is a former Lincoln Cathedral stonemason and has nearly 30 years of experience in architectural stonework and carving. According to her biography, she served her apprenticeship at the cathedral and is a holder of a distinction in Advanced City and Guilds Stonemasonry—the highest designation obtainable.

My flight touched down in London early in the morning of Sunday, May 13, which gave me three days to get over jet lag before class began on Wednesday. I spent the first day in London at the British Museum. As I strolled the labyrinth of galleries filled with Egyptian mummies, stones from the Parthenon, and once-buried Roman treasures, I kept my eye out for letters carved in stone. The museum did not disappoint.

Sample of carved stone in British Museum; when “erasing” someone from history, their name might be obliterated from stone to ensure their name was lost to time.

The next day I traveled by train to Lincoln. I crafted my schedule so I could spend a full day exploring the city before sequestering myself inside Eilidh’s workshop. The city of Lincoln has two notable landmarks: a walled castle and the third-largest cathedral in England. I lived in London in 1988, then again in 1991–1992. I didn’t expect my deep affection for St. Paul’s Cathedral could ever be challenged, but the Lincoln Cathedral, is quite simply, breathtaking.

Interior of Lincoln Cathedral.

LETTER CUTTING: DAY ONE

I had imagined Eilidh would be a roundish, frumpy, middle-age woman. Boy, was I wrong. Eilidh rolled up to her workshop on a hot-pink motorcycle. Curly red hair was pulled into a ponytail atop her head. She had tattoos up and down her arms and a ring through her septum. “Frumpy” was not a word that fits Eilidh.

One other student joined us, an Englishman named Colin. It was Colin’s third and last day of an ovolo class. An ovolo is round convex often quarter-circle molding. It’s the kind of shape you might find on a fireplace hearth. Colin was a retired engineer, but he told me he had always wondered if he should have been a stonemason instead. Now, in retirement, he was finally getting his chance to work with stone. Throughout the day, Colin worked slowly and carefully as he refined his ovolo.

Colin working his ovolo stone with Eilidh’s guidance.

Eilidh placed a piece of limestone on a bench a few feet away. The “bench” was a sturdy, wooden freestanding table with a work surface about 16” square. Eilidh grabbed her chisel and a dummy (a mallet) and effortlessly carved a thin, straight groove into the stone.

She handed me a chisel and dummy and I tried to do the same. Tried.

When carving, the left-hand holds the chisel at both a 90° angle to the cut while also maintaining a 45° angle to the (future) v-shaped groove. Proper position is critical: an improperly positioned chisel can result in an over-cut (flattening) of the desired groove, or under-cutting/notching the opposite side of the “v.” Meanwhile, the right hand holds the dummy and strikes the chisel with just the right amount of force. While that happens, your eye isn’t supposed to look at the chisel or the mallet. Instead, Eilidh told me, I needed to look ahead of the cut to ensure future movements maintained the correct angle and force. Other cues helped inform the success of each movement: the sound of the chisel on stone, the direction and velocity of the tiny stone chips.

But, that was too much to keep track of all at once, and my thin, straight grooves turned out to be neither thin, nor straight.

Eilidh’s effortless carving was, in fact, a result of many years of effort.

Some of Eilidh’s work, as seen in her studio.

That afternoon, Eilidh had me try my hand at curved shapes. First, I carved an “s” shape with a uniform-width channel. Then she had me carve a different “s” shape that narrowed as the curved lines converged. Surprisingly, cutting a curve came more naturally to me than cutting a straight line. Eilidh seemed unsurprised. She often observed that people could do one but not the other.

By the end of the day I had a stone with a collection of grooves: some curved, some straight-ish. None of my grooves had a perfect center spine flanked by 45˚ walls, but I felt it wasn’t a bad first day.

The assignment for the evening was to come up with a word or phrase, 8–10 letters long in total, that I’d use for my “final project.”

The walk from Ministry of Stone back to my hotel.

LETTER CUTTING: DAY TWO

In the morning, Eilidh showed me how to cut terminals. She chose one of the straight grooves I had made the day before and effortlessly chiseled the end so it ended with a square triangular cap.

Like the day before, I picked up the chisel and dummy and tried to mimic her steps.

The concept of cutting a square terminal was straight-forward enough. However, placing the chisel in precisely the right place at precisely the right angle was easier said than done. All of my lines ended with an incremental flare at the end.

The flared ends made me think of Optima, Hermann Zapf’s ubiquitous san serif font. Optima’s letterforms flare ever so slightly. To be honest, I had never been a fan of the flare. During the class, however, as I noticed how light played with the letters, the flare—which, don’t get me wrong, I didn’t intend to add—added an element of grace.

After practicing terminals, Eilidh demonstrated how to make serifs (a.k.a. intentional flares). Eilidh didn’t seem to be a fan of serifs, though, remarking she was certain serifs had been invented to cover some stone carver’s mistake.

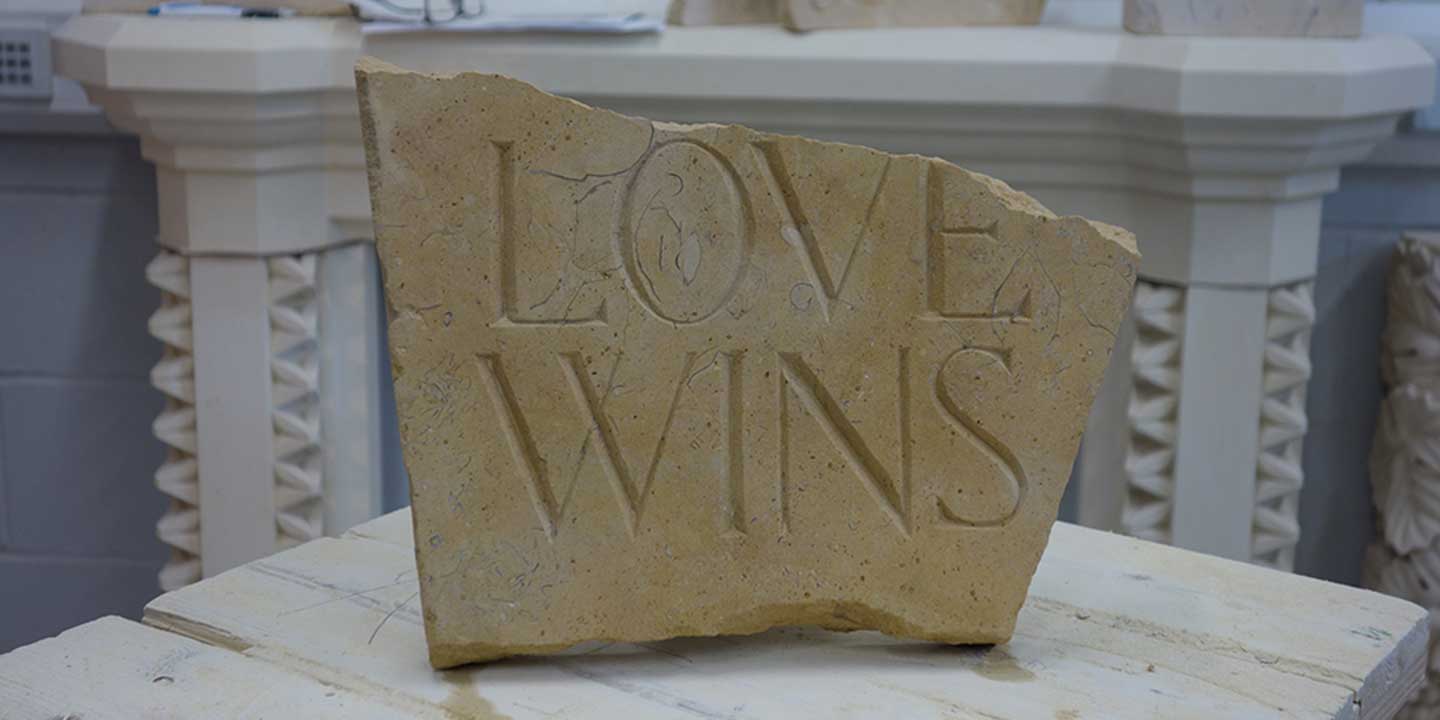

After a short break for lunch, Eilidh placed a new piece of buttery limestone on my bench; I’d work this stone for the next day-and-a-half. Eilidh asked for the 8–10 letter word/phrase she had asked me to think about the night before. I wanted the letters to provide the utmost challenge, which meant including both an “O” and an “S.” And I liked the notion of including a cross-stroked “W.” So, the phrase I chose was “LOVE WINS.” I penciled the letters onto the stone, but before starting to carve, Eilidh suggested a revision to the layout: she thought it would be interesting to have the letters run off the top edge, as if the stone had broken off. I liked the suggestion, in part because the revised layout provided the additional challenge of carving right to the edge.

After revising the penciled-in letters, I picked up the chisel and dummy began to carve. By the end of the day, the straight grooves of the “L” “V” “E” “W” and “N” had been carved. Unfortunately, an unintentional nick in one of the sidewalls of the “N” meant the groove needed to be widened to fix the flaw. (Eilidh helped rescue the situation before I made it worse.)

Ultimately, the wider “N” also meant I needed to widen the “L,” “V,” “E,” and “W” to match the “N.”

Eilidh fixing the nick in my letter “N.” Eilidh is left-handed, so she holds the chisel in her right hand and the dummy in her left hand.

LETTER CUTTING: DAY THREE

The day began with Eilidh and I discussing the best way to tackle the curves of the “O” and the “S.” I appreciated we could talk about letterform theory, and things like the size of the overshoots. After refreshing the pencil lines that had been roughed-in the day before, I tackled the “O.” To my surprise, it turned out more symmetrical than I expected. And the curves of the “S” were smoother than I would have guessed possible after only two-days’ practice.

The balance of the day was spent carving the crossbars of the “E” and “L,” then carving the thin lines of the ”V,” “W” and “N,” then refining the terminals and various lines here and there.

At the end of the day, Eilidh cleaned the stone and we critiqued the work. The letters have more than their share of flaws and inconsistencies. The “N” is still wider and deeper than other letters, the terminals (or absence of) vary in style, and the thinnest cuts are far from straight. But, considering the fact I held a chisel for the first time just two days earlier, the work wasn’t bad. And it met the goal of doing tactile work with care and reverence. In that regard, the work perfectly met my goal.

Want to see more of Eilidh’s work? Follow her Instagram account.

Want to check out class options? Visit the Ministry of Stone website.